1910s

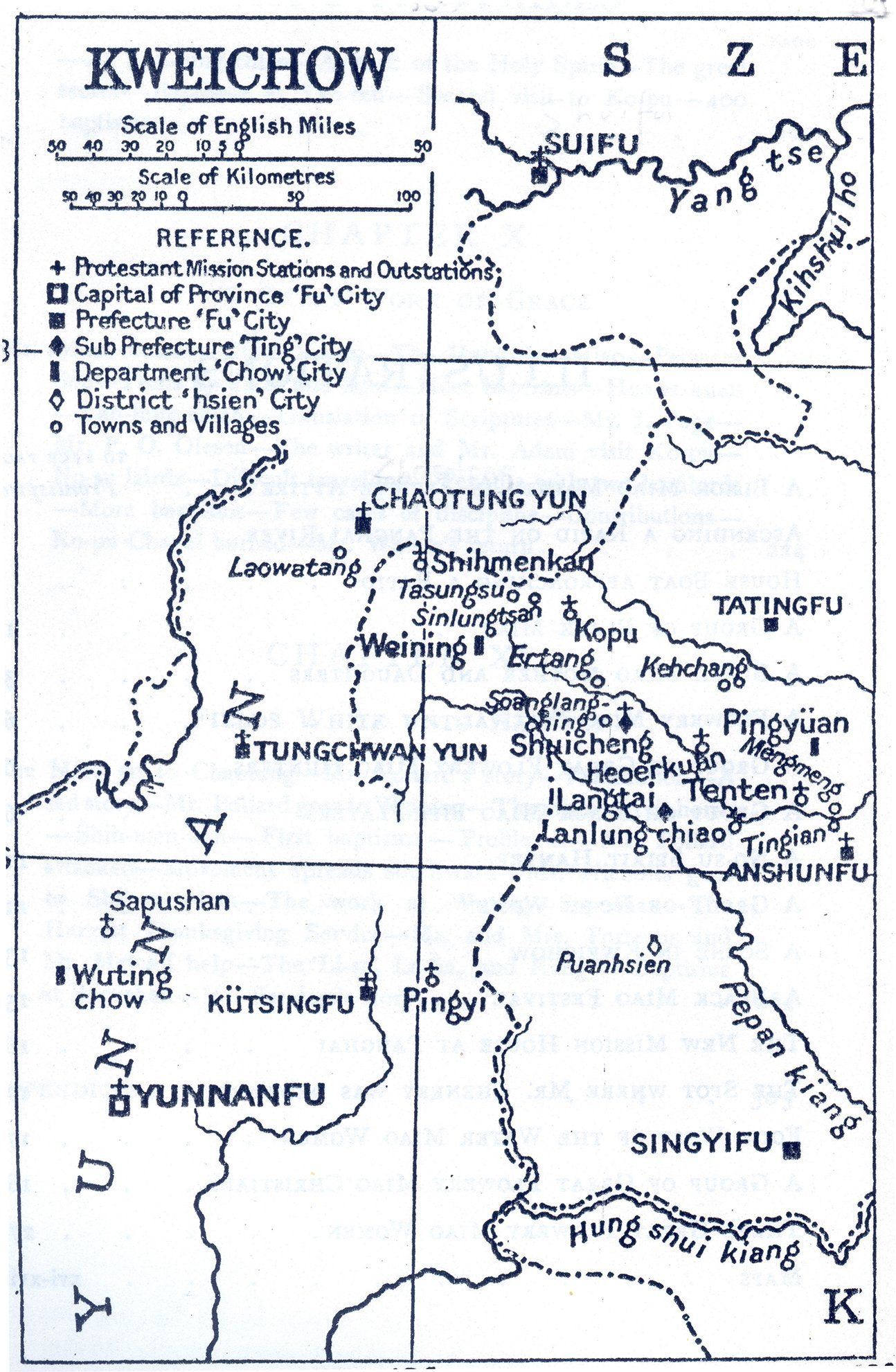

A 1910 map showing all the mission stations in western Guizhou.

A Province Divided

The new decade of the 1910s got under way with a promise of great things for the Church in Guizhou, although several barriers needed to be overcome for the gospel to gain widespread acceptance. A division existed between people living in the cities, where progress had been excruciatingly slow, and those living in rural villages who were generally much more receptive to the claims of Christ.

A further division existed between western areas of Guizhou, where promising breakthroughs had occurred, and the eastern half of the province which remained spiritually barren with very few Christians and little gospel witness.

The most prominent division in Guizhou, however, occurred along ethnic lines. Some groups, including the Han Chinese, were adherents of organized religions such as Buddhism and Daoism, causing them to be more resistant to Christianity. On the other hand, the spirit and nature worshipping tribal animists appeared to have few hindrances to wholeheartedly embracing Jesus Christ once they heard the message in a clear manner.

In the 1910s, Guizhou was an anomaly among the provinces of China in that just one missionary organization, the CIM, almost exclusively worked in the province, although in the previous decade the Methodists had also established a base in northwest Guizhou. Other mission groups would soon arrive, giving an overall boost and helping spread the gospel to more people.

Dangers, Toils and Snares

The Qing Dynasty unravelled in 1911, and China was thrown into social disorder and lawlessness, with remote Guizhou not spared from the chaos. The missionaries and their converts began to encounter severe danger.

In 1911, five cities in Zunyi Prefecture staged an open rebellion against Chinese rule, with the people massacring a General and 200 of his troops. With the economy in complete disarray, thousands of men in Guizhou turned to banditry, robbing and murdering innocent victims. The lawlessness continued for many years before the authorities were finally able to get it under control.

Government leaders in Anshun were concerned for James Adams' safety, and they insisted that armed soldiers be sent to protect him on his travels. At first Adam resisted the idea, but he relented when the violence worsened. On the first few journeys, however, Adam discovered that the soldiers sent to accompany him were not used to trekking for days over high mountains, and they often lagged many miles behind. The missionary pressed on, only reconnecting with his 'protectors' days later at prearranged stops along the way.

During one gruelling six week journey, Adam and his colleagues were tipped off that a massive group of 500 bandits was hiding in a large cave near the road they intended to travel down the next day. They would have walked right into the ambush but for the help of local Christians, who led the missionaries on a long detour through another district to avoid the murderers.

During the social chaos and turmoil, Adam's greatest concern was for the Miao churches. In 1912 he wrote:

"If the newly-interested Miao enquirers were only grounded in the Truth, persecution would, no doubt, help them, but they are for the most part only beginners, and one fears lest they should not stand firm in the face of such fierce opposition as they are called to endure. Over 1,000 families have been enrolled as enquirers. Please pray much for these dear, persecuted Miao enquirers."

The Pollard Script

As the gospel continued to flourish among the A-Hmao, it became apparent that the believers needed God's Word in their heart language if Christianity was ever going to make a lasting impact. Previously the A-Hmao believers had tried to read the Chinese Bible, but it was completely foreign to most of them, and it consequently failed to impact their hearts or change their lives.

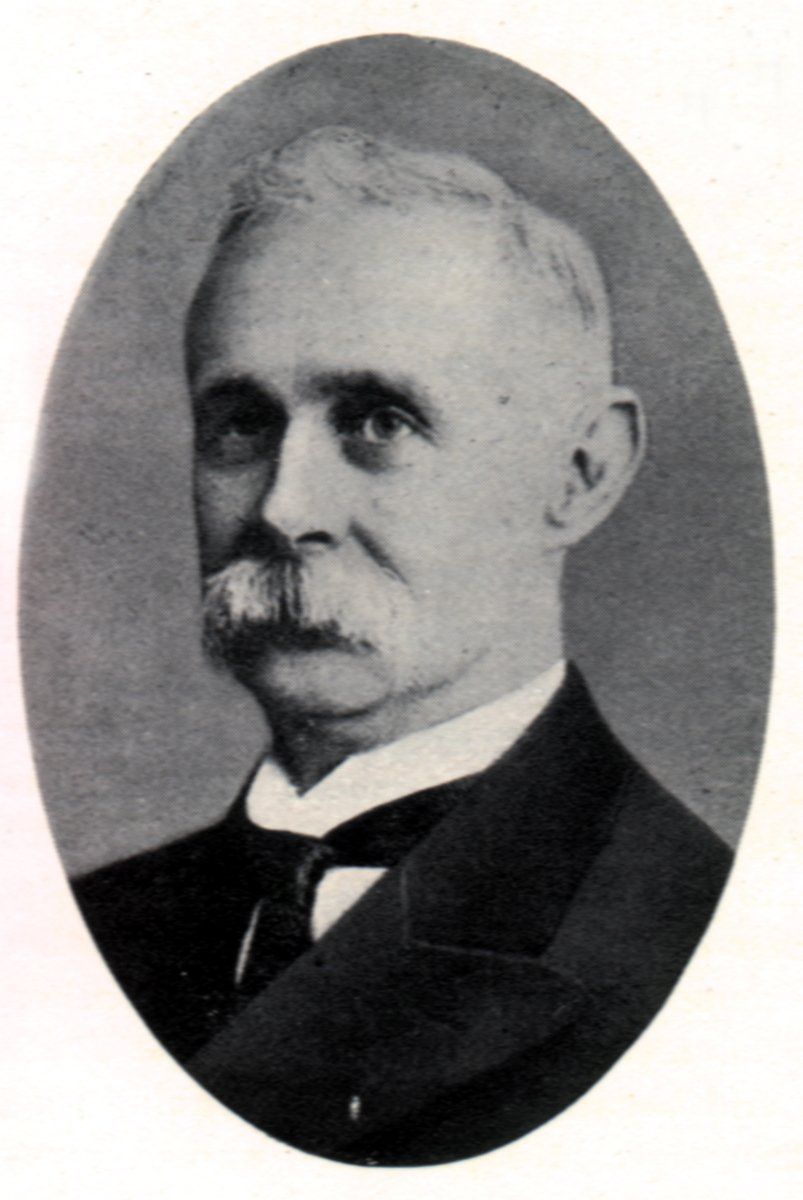

Samuel Clarke in 1916.

The gifted James Adam found himself at the forefront of a new initiative to translate God's Word into A-Hmao. He began work in 1908, and the entire New Testament was completed and printed in 1917, using Roman letters to represent the A-Hmao words. Samuel Clarke, who was also involved, summarized how the A-Hmao Bible gradually emerged:

"Compared with learning to read Chinese characters, it is very easy for them to read their own language phonetically, written in Roman letters. In May 1909, the first copies of Mark's Gospel arrived from the printer. Later on, the Gospel of Matthew was printed, and the Gospel of John, with his Epistles, is now in the hands of the printer....

Soon the whole New Testament will be in the hands of the A-Hmao Christians. They are eager to learn to read, and those who can read are zealous in teaching others. Very soon they will be a reading community."

At the same time, however, the genius missionary-linguist Samuel Pollard was pondering whether the A-Hmao might better understand God's Word by using a different orthography. While he was praying, he remembered reading about a unique script used to translate the Bible into the Native American Cree language.

After tweaking the Cree script to suit the tonal vernacular of the A-Hmao, Pollard began translating the Scriptures, hoping to make it as simple as possible for the uneducated tribesmen to learn. When the first portions became available, the believers were overjoyed. Because the new alphabet was so simple to learn, soon dozens of A-Hmao villages were holding Bible study classes. The Pollard script quickly gained favor among the A-Hmao Christians, and James Adam's Roman version soon fell into disuse.

A sample of the Pollard script created for the A-Hmao people.

Having the Bible added a great deal of dignity to the A-Hmao people, who were amazed that God had not forgotten them, and that He loved them so much to have sent them His precious Book in their own language.

The A-Hmao were the first minority group in Guizhou to have the Scriptures in their language, and the Pollard script Bible is still widely used among them today. Alas, a century later, the A-Hmao remain one of only a small number of minority groups in all of China with the Word of God available in their own written language.

The Shui and other Tribes

The Shui ethnic group in southern Guizhou was first visited by French Catholic missionaries in 1884, and by the early twentieth century there were some 5,000 Shui Catholics in 30 churches. An anti-Christian movement in 1906, however, resulted in many of the Shui church leaders being put to death, and the rest of the believers fell away.

Evangelical missionaries first contacted the Shui in 1910. A small group of Shui men heard that the missionaries were visiting Miao churches in the area and, eager to understand the Christian message, they sent delegates to meet the missionaries, who reported:

"A new interest has sprung up among the Shui.... Hearing we had come, some of these men travelled overnight fearing we might have left before they met us. A few of these Shui were down at our Chinese New Year's conference. A son of the headman of that district is studying in our Anshun school this year.... If the work is going to spread out in this way, the Lord will need to send more workers."

Sadly, it appears that no new workers came to reach the Shui, and little mention was made of them in subsequent years and decades following this initial contact. Tragically, for nearly 100 years few Shui people heard about Jesus Christ, and it was not until the twenty-first century that an effective church emerged among this gentle and friendly group, which today numbers approximately 500,000 people.

Although the missionaries were thrilled by the spiritual progress among several Miao groups, dozens of other neglected tribes lived scattered throughout the never-ending mountains and valleys of Guizhou. Some missionaries, having been trained to think rationally at seminaries in their home countries, were shocked by the spiritual darkness they encountered when they attempted to introduce the gospel to tribesmen for the first time.

William Hudspeth commented, "As a rule I don't believe in devils but these wizards seem to have great communications with a whole world of demons." He went on describe some of the supernatural feats done by these men, including putting white-hot chains around their necks without being harmed.

Four Christian women from a tribe known as the 'Wooden Comb Miao' near Anshun in 1914.

The Anshun missionaries came across several other tribes during their frequent travels throughout Guizhou. One Miao tribe they called the 'Wooden Comb' or 'Lopsided-Comb' Miao. This group lived about 20 miles (32 km) south of Anshun, and were so-named because of their women's elaborate hairstyles. In 1914 Adam was thrilled to report:

"Two delegations from the Wooden Comb Miao came down the mountains asking for teachers to go and teach them the gospel. Peter and Timothy returned with them.... They are now busy up in the mountains telling forth the old story of Jesus and His love....

Travelling by another route, we came upon a new tribe called the Big-Horn Miao.... We stopped, and spoke to them first in Chinese and then in one of our Miao dialects. They did not run away, but stood and listened to what I had to tell them.... Oh when shall all the very long, waiting, lost tribes hear the message?

Praise God for the many that are now hearing and learning the gospel. How the heart of the Lord Jesus Christ must rejoice over so many of His lost, wandering sheep finding their Good Shepherd at last."

Adam visited another village just one month later, where he noted, "At this place Red-Turbaned, Water, and Wooden Comb Miao joined the meetings. The first-fruits from among the Wooden Comb Miao were baptized."

The Only Doctor in Guizhou

A boat with a party of Guizhou missionaries on board in 1913.

At the time there were 31 missionaries in the province; 27 with the CIM and four Methodists.。

A boat with a party of Guizhou missionaries on board in 1913. At the time there were 31 missionaries in the province; 27 with the CIM and four Methodists.

In 1913 the population of Guizhou was estimated at between 12 and 18 million people, but not a single doctor worked in the entire province. Stirred by the reports of James Adam and others, a British doctor, Edward Fish, surrendered his life to God's service. Compelled by the love of Christ, Fish abandoned his financially-lucrative career and relocated to the other side of the world to serve the impoverished people of Guizhou.

After gaining his orientation with the Adams in Anshun, in August 1913 Fish joined the intrepid missionary on one of his arduous journeys among the tribes. Having read the remarkable accounts of revival published in magazines, Fish had a romantic image in his mind of the work, but the harsh reality of what life was like in rural China soon struck him to the core of his being. The doctor wrote from one of the first villages they stopped at:

"I arose early—about five o'clock—hoping to have a quiet time by myself before the duties of the day began. However, it was to be otherwise, for I had no sooner arisen than patients began to come and continued all day long. Only with the greatest difficulty was I able to get away for my meals. For over 12 hours I was just as busy as I could be. When I returned from dinner, they were lined up outside the door for a considerable distance, while the inside was packed with men, women, and children waiting for a chance to press their way up the ladder where I was at work. I must have seen nearly 400 patients."

Although Dr. Fish's treatment was free to sick people, the generous-hearted Miao felt it wasn't right to receive treatment without giving something in return. At another village a few days later, Fish was excited when the first batch of mail from home caught up with him. He sat down on a bench intending to read his letters, but was soon completely surrounded by those in need. He wrote:

"One man handed me a fowl, another came with a basket of eggs. This proved too much, and I arose and took my place where for three days I sought to minister to their needs. At this place I received over 500 eggs, 20 chickens, several pots of honey, baskets of potatoes, green corn, beans, etc."

On one occasion, Fish was asked to visit a poor family in great need. He entered their dark and dingy hovel, and was scarcely able to see as he carefully made his way around the wet mud floor. All of a sudden he stepped on the foot of a small nine-year-old boy, who was lying naked with his back turned toward the fire. "It was most pathetic to see a child of such tender years lying on the damp mud floor in the grip of a disease. He strongly resisted every effort I made to examine him," wrote the stunned doctor, before his attention was attracted to another object. He recalled:

"Turning back another ragged and filthy rug...I beheld a sight I believe I shall never forget. A woman lay there—dying. She, too, was lying on the damp ground, clad in the scant remnant of what was once a garment. Her hair was dishevelled, her form emaciated, both eyes glued together with a copious discharge, and her four limbs so entangled that I could scarcely find a place to put my stethoscope on her chest. She made no resistance. Once she tried to speak, but her strength was too far gone.... The time of her departure was at hand....

All that passed through my mind at that time can better be imagined than described. Gazing upon the representatives of three generations, it seemed as though I never realized before what claims these people have upon me. How appalling their poverty! How great their need!"

James Adam was a wise and loving man. He knew the new recruit was overwhelmed by his first journey, so when they returned to Anshun, Adam spent much time taking care of Fish and praying earnestly for him. Adam realized that treating the sick on long itinerant journeys was not the most productive way to utilize the doctor's skills. He decided to open a small hospital in Anshun, where people from throughout the region could come to be treated and receive medicine. When the hospital opened in 1914, Adam joyfully wrote:

"It is my great privilege to open the first hospital in this entire province.... Great as the medical need is, it cannot be compared to the spiritual darkness—which is appalling. Our hospital and dispensary work must always ever be secondary in importance to the real needs of the people. While doing all that is within our power to alleviate their suffering and to heal their diseases, we must never forget that we are here, primarily, as ambassadors of our Lord Jesus Christ. May He give us the needed grace to be successful 'fishers of men,' and that when the day's work is done it may be 'well done'. "

A Decade of Growth

The initial years following the sudden loss of so many influential leaders were difficult ones for the Church in Guizhou. More than 10,000 A-Hmao Christians inhabited the areas of northwest Guizhou and adjacent parts of Yunnan when Adam and Pollard perished in 1915. The sudden removal of the duo struck the fledgling churches like a hammer blow, and in the next few years many who had placed their trust in the missionaries instead of Jesus Christ fell away from the faith. William Hudspeth noted, "After Pollard's death there was a recrudescence of drunkenness, immorality and superstition."

The spiritual decay was exacerbated in 1918, when the worst famine in living memory struck the Stone Gateway area, leaving many A-Hmao feeling disenchanted toward God.

With the benefit of hindsight, however, the quality of the foundation laid by Adam and Pollard can be seen by the fact that more than a century after their deaths, approximately 80 percent of both the 400,000 A-Hmao (Big Flowery Miao) people and the 130,000 Gha-Mu (Small Flowery Miao) people continue to walk by faith in the Son of God.

Statistically, the Evangelical churches in Guizhou had experienced a decade of unprecedented growth. In 1904 the total number of Evangelical believers in the province was just 123, but by 1919 it had mushroomed to 20,873, a number 170 times greater over the 15-year period.

Catholics had also enjoyed significant growth in Guizhou, and they continued to enjoy numeric dominance over their Evangelical counterparts. In 1907 there had been a reported 25,368 believers in 106 Catholic churches throughout the province.

Fourteen years later in 1921, when the next reliable survey was conducted, the Catholics had grown to 35,286 members in 286 churches, meaning there were nearly four times as many Catholics as Evangelicals in Guizhou at the time.

© This article is an extract from Guizhou - The Precious Province (Simplified Chinese) 贵州省 “宝贵之省” (简化字). You can download this or any of our other Chinese books and e-books from our

online bookstore.